The Doctrine Of The Builder State: Norway in the Next World Order

A strategic diagnosis and proposed doctrine for reestablishing national strength in an era of global competetion

1. Executive Summary

Norway projects stability—energy-rich, capital-secure, and socially cohesive—but faces strategic drift. Its industrial base has eroded, sovereignty is diluted by transnational frameworks, and leadership prioritizes continuity over transformation.

This brief outlines:

Systemic roots of Norway’s strategic inertia

A doctrine for renewal via subsidiarity, sovereignty, and builder-class leadership

Norway’s potential as a sovereign Arctic outpost for the West

Implications for U.S. strategic planning in the North Atlantic and post-global economy

Norway holds unique leverage: energy sovereignty, seabed minerals, Arctic launch capabilities, a global merchant fleet, and geopolitical flexibility outside EU constraints. These assets are underutilized due to a lack of conviction and mission-driven leadership. The U.S. should view Norway as a latent geostrategic node, capable of anchoring Western resilience in a multipolar world, if realigned around purpose.

2. Strategic Diagnosis

Managerial Capture

Norway’s leadership class is drawn from system-loyalists: administrators, not builders. Selection favors incrementalism and ideological safety. This class excels at managing stasis but fails in moments requiring decisive transformation.

Energy Wealth Without Strategic Doctrine

Oil and gas revenues created a passive economy. Rather than using energy sovereignty to build strategic infrastructure or supply chains, Norway settled into redistribution and financial stewardship.

Meritocracy Without Conviction

The system promotes those who perform well within the system—not those who challenge it with conviction. Over time, belief in the system replaced belief in a purpose beyond it.

Globalization Eroded Sovereignty

Norway outsourced large segments of its industrial policy, food security, and regulatory sovereignty to international institutions. What remains is a sovereign façade with outsourced content.

3. The Drift Beneath the Surface

Norway's strategic failure is rooted in its philosophical drift. The next phase of nationhood must be built on a deeper understanding of what enables resilient adaptation to a changing environment.

What is success?

From a historical perspective, luck has often been viewed as a variable to be overcome rather than a force to be relied upon. Thomas Jefferson famously remarked, “I’m a great believer in luck, and I find the harder I work, the more I have of it,” emphasizing the role of effort and intentionality over chance.

In the post-war era, however, success increasingly came to be understood as a product of context. One was considered fortunate to be born in the right place, into the right family, or to have access to the right networks. This perspective was not without merit. The international system that emerged after World War II functioned much like a machine—producing favorable outcomes for those who understood its mechanisms, knew how to operate it, and could identify where to “insert the coins.”

Yet systems are not permanent. When such a machine no longer functions effectively, no longer delivers predictable outcomes, or ceases to serve the interests of its designers, it must be replaced. This transformation alters not only the rules of the game, but also the foundational ingredients of success.

Success from a builder’s perspective

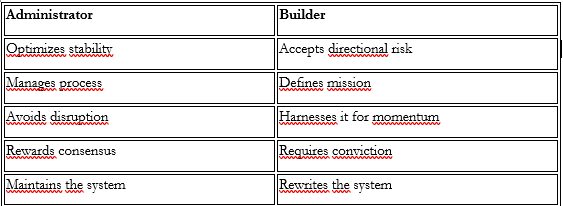

Transformational change is fundamentally a function of leadership—not management. While management excels at preserving structure, reducing variance, and optimizing existing systems, it is ill-suited for moments requiring directional shifts. When the system itself must be replaced, not merely improved, leadership becomes indispensable.

Systems, by their very nature, are optimized for survival, stability, and efficiency. As a result, they tend to reward those who master the art of administration: individuals adept at maintaining continuity, navigating complexity, and minimizing disruption. These are the administrators—custodians of the status quo and when politics becomes a career, leadership becomes impossible. Norway’s democratic machinery promotes those who manage, not those who build. The result is slowness, shallowness, and civil fatigue.

Builders emerge in moments of discontinuity. They are not selected by the system, but rather compelled by conviction to challenge it. Builders are oriented toward possibility rather than preservation. They do not seek to diversify away from risk, but to move decisively in a chosen direction. For them, success is not a matter of favorable context or fortunate timing; it is the outcome of purposeful action, often in defiance of conventional wisdom.

This distinction between administrator and builder reflects more than just a difference in skillset—it represents a fundamental divergence in worldview. The administrator operates within existing structures, mastering the rules of the game. The builder rewrites the rules, or creates an entirely new game.

In periods of systemic stability, administrators dominate. In times of upheaval -when the system no longer delivers expected outcomes - builders become indispensable. Understanding which archetype a system cultivates, and which it suppresses, is critical to anticipating how that system responds to disruption—and whether it can survive transformational change at all.

How systems evolve

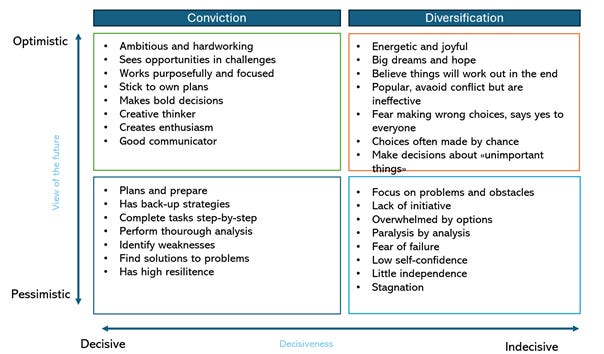

Systems—whether empires, corporations, or international orders—do not exist in a vacuum. They evolve over time, shaped by how they respond to opportunity, threat, and success. Using a framework based on two core axes—decisiveness and view of the future (optimism vs. pessimism)—we can model the behavioral psychology of systems across their lifecycle.

The matrix consists of four strategic dispositions:

Decisive + Optimistic (Builder)

Decisive + Pessimistic (Maintainer)

Indecisive + Optimistic (Dreamer)

Indecisive + Pessimistic (Avoider)

This framework can be used to trace how a successful system, born out of conviction, transitions over time toward stagnation and eventual replacement.

1. Emergence: The Builder Phase (Decisive + Optimistic)

Every enduring system begins with conviction. This phase is characterized by bold leadership, visionary goals, and a willingness to act decisively in the face of uncertainty. Builders emerge not because conditions are ideal, but because they are willing to shape conditions to fit their purpose.

Success is rooted in agency, belief, and sacrifice.

Structures are created, not inherited.

Power is tied to the ability to act, not to administer.

Historical parallels: The Roman Republic, the U.S. post-1945, post-colonial independence movements, and President Donald Trump 2.0.

Strategic signature: High trust, central leadership, directional clarity.

2. Consolidation: The Maintainer Phase (Decisive + Pessimistic)

Once initial goals are achieved, systems begin to institutionalize their success. Processes are introduced to standardize outcomes and manage risk. The focus shifts from expansion to preservation. While still decisive, the system becomes increasingly preoccupied with stability and control.

Diversification is introduced to hedge against shocks.

Bureaucracies grow to manage complexity.

Risk is seen as something to be contained, not pursued.

Strategic benefit: Resilience and continuity.

Strategic risk: Innovation slows, boldness declines.

Historical parallels: Imperial Rome under Augustus, Cold War-era U.S. containment strategy.

3. Diffusion: The Dreamer Phase (Indecisive + Optimistic)

In this phase, the system retains optimism, but loses the clarity and courage to act decisively. It becomes performative—governed more by symbols, narratives, and appearances than by tangible outcomes. Financialization replaces production, and law begins to overtake leadership as the primary mechanism of coordination.

Systems shift from building substance to managing perception.

Financial abstraction becomes a substitute for material creation.

Legality replaces legitimacy; compliance replaces conviction.

Law, once a tool for enabling order, begins to restrict adaptive action.

Process is elevated above outcome; risk is systemically suppressed.

The result is a hollowed center: institutions speak of progress but are unable to operationalize it. Decisions are deferred, diluted, or outsourced—creating a leadership vacuum filled by administrators with no mandate to act.

Historical parallels: The late British Empire’s bureaucratic expansion, U.S. post-industrial economy, EU technocracy.

Strategic outcome: Drift and disconnection. Momentum remains, but direction is lost.

4. Decline: The Avoider Phase (Indecisive + Pessimistic)

In the final stage, the system is driven not by vision but by fear. It no longer believes in its capacity to shape the future and instead seeks only to manage decline. Law becomes the last source of authority—but also a cage. When every action must be justified procedurally, nothing bold can be done.

Legalism replaces leadership. Authority hides behind regulation.

The system suffocates under its own rules.

Paralysis by analysis becomes standard operating procedure.

Institutions exist to perpetuate themselves, not to serve a mission.

The avoidance of conflict takes precedence over the pursuit of value.

The most competent actors now focus on navigating the system, not changing it. Risk-taking is punished. Innovation is bureaucratized. Citizens, employees, or allies disengage—not out of apathy, but out of a growing sense that the system no longer serves them.

Historical parallels: The Western Roman Empire before collapse, late-stage EU institutional gridlock, contemporary U.S. administrative overreach.

Strategic consequence: Strategic paralysis followed by external shock or internal rupture. The system either fragments or is overtaken by a leaner, conviction-driven alternative.

A Predictable Cycle

What begins in conviction, ends in avoidance—unless the system can renew itself. Each quadrant in the matrix reflects not only a type of leadership, but a collective disposition toward risk, time, and identity.

Understanding where a system currently sits in this matrix is crucial for determining its future viability. If it is drifting toward the dreamer or avoider phase, internal reform will require the reintroduction of builder traits: clarity, decisiveness, and belief in the capacity to act.

Systems are never static. The only question is whether they evolve by design—or by collapse.

Strategic Disposition and the Trade Deficit Trap

Over the past century, the global economy has shifted from hard currency systems—where power was tied directly to metal reserves and trade balances—to a fiat-based order where liquidity can be manufactured on demand. But while fiat currency allowed nations to delay collapse, it did not eliminate strategic constraints. Instead, it obscured them.

In a hard money world, running a trade deficit meant losing wealth and sovereignty. Silver left the country, purchasing power declined, and external enemies gained leverage. Military contraction, political instability, and foreign subjugation often followed. The only strategic protection was to run a surplus—to produce more than one consumed.

The shift to fiat currency, central banking, and dollar hegemony allowed deficit nations—primarily the U.S. and its allies—to project power without production, issuing debt to fund consumption and defense. But as debt grew and supply chains globalized, real economic substance—jobs, manufacturing, and critical technology—migrated abroad.

When crisis struck (COVID-19, war, embargo), these nations discovered the weakness of the system they had created: they could print money, but they could no longer produce what they needed.

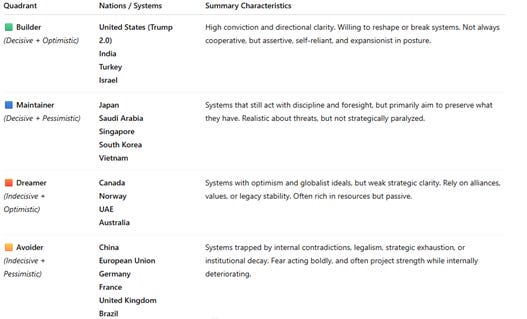

The Strategic Disposition Matrix and Economic Structure

The Strategic Disposition Matrix (Decisiveness × Outlook) helps explain how countries behave under these pressures. It also reveals how monetary architecture and trade positioning form national psychology and strategic posture.

Builder (Decisive + Optimistic)

Characteristics: High agency, directional strategy, belief in national renewal

Economic posture:

Often reacting to previous overexposure to deficits

Rebuilding industrial base (re-shoring, tariffs, subsidies)

Sees trade as power

Accepts confrontation as necessary for autonomy

Examples:

United States (Trump 2.0): Embracing mercantilism, decoupling from China, industrial policy revival

India: Nationalist economic strategy, protecting domestic markets while building export capacity

Turkey: Strategic autonomy across energy, defense, and diplomacy

Israel: Tech sovereign, producing value at home, not dependent on debt-based consumption

Builders break free of the deficit trap by forcefully reasserting productive sovereignty.

Maintainer (Decisive + Pessimistic)

Characteristics: Technocratic, risk-averse, focused on stability over ambition

Economic posture:

Often surplus nations (e.g. Japan, South Korea, Singapore)

Highly industrial, export-dependent

Aware of demographic or geopolitical decline

Examples:Japan: Huge trade surplus, productive economy, but aging population and stagnant politics

South Korea: Technologically competitive, but deeply security-dependent

Saudi Arabia: Wealthy, decisive, but hedging against post-oil future

Maintainers are stable, but lack the optimism needed to reimagine their place in a new order.

Dreamer (Indecisive + Optimistic)

Characteristics: Idealistic, multilateralist, reactive

Economic posture:

Often wealthy, consumption-driven

Trade deficits tolerated as long as system is peaceful

Lacks industrial ambition, depends on others for security and production

Examples:Canada, Norway, Australia: Resource-rich and system-trusting

UAE (on edge): Trying to invest its way into productive power without strong internal base

Dreamers believe the system will hold, and don’t act until it breaks.

Avoider (Indecisive + Pessimistic)

Characteristics: Trapped by institutions, constrained by fear, losing strategic clarity

Economic posture:

Often with persistent trade deficits and no reindustrialization plan

Increasingly reliant on debt and imports

Bureaucratized to the point of paralysis

Examples:China (2025): No longer confident. Losing industrial edge, hoarding capital, copying U.S. mercantilism in panic

Germany / EU: Regulatory overreach, deindustrialization, energy dependence

UK, France, Argentina, Brazil, Iran, Ukraine: Institutional decay, economic dependency, and/or internal instability

Avoiders are caught in the deficit trap, unable to produce, afraid to confront their decline, and politically incapable of coherent redirection.

Final Observation

The only real hedge against mercantilism is to become one—but not every country can run a trade surplus. In a world where fiat masking has run its course, mercantilist rearmament leads to systemic conflict.

The return of mercantilism is not just an economic phenomenon—it’s a strategic one. Nations are realizing that production equals power, and debt-fueled consumption is not sovereignty. Those who act, and build, will shape the new order. Those who hesitate will serve it.

For Norway, entering the first phase of a new global architecture will require decisive shifts in policy, mentality, leadership, and model of governing.

4. Adapting to a new reality

Managerial capture and change management

At the heart of every successful change process lies subsidiarity: the deliberate devolution of power from centralized authorities to those best positioned to act—those with the greatest situational awareness, accountability, and proximity to the problem.

Change is driven by leadership, not management. If decentralization unlocks transformation in large, complex organizations, why should nations be any different when facing the need to reshape their economic or societal models?

Change is inherently energy-intensive, but energy is not a fixed resource. It expands when fueled by inspiration, recognition, and tangible results. Yet our political class consistently chooses mass, volume, and centralization—over precisely those things that generate momentum and renewal. Why?

Because the system is optimized not for transformation, but for survival, stability, and efficiency. It rewards the cultivation of administrators, not builders. It selects for individuals skilled in managing stasis—not those capable of initiating bold directional change.

These are leaders chosen for their ability to deliver incremental gains—not for embracing risk, achieving breakthroughs, or reinventing systems. Their pursuit of merit through formal education, deep specialization, and alignment with global frameworks reflects a core bias: a preference for order over disruption, and continuity over renewal.

This is why they double down on centralization, volume, and mass. It’s not just habit—it’s their nature. Stability and incrementalism define their worldview, from personal career paths to their embrace of globalization. And herein lies the uncomfortable truth:

This class is structurally—and temperamentally—unfit to lead transformation.

And yet, they occupy the very positions from which transformation must be initiated.

Fiat Governance and the Trade Deficit Illusion

This same logic has governed how nations managed economic decline under fiat currency systems. When money was still silver and gold, trade deficits were fatal. Wealth left the country. Purchasing power collapsed. And so did the state.

In that world, power came from producing more than you consumed—not printing more than you owned.

The arrival of fiat currency, central banks, and sovereign debt merely delayed collapse. Deficit nations could inject liquidity, stimulate consumption, and preserve the illusion of prosperity. But they were no longer producing. They became hollowed-out consumer economies, exporting capital in exchange for goods they no longer made.

When crises hit—pandemics, wars, or supply chain disruptions—these nations were exposed. They lacked the capacity to produce what they needed at speed, scale, and independence.

And yet, the administrative class in charge of this decline responded not by devolving power—but by centralizing it further.

Instead of reindustrializing, they managed the optics of decline. Instead of rebuilding resilience, they issued more debt. The result was the entrenchment of managerial regimes whose power depends on stasis, even as the systems they govern become structurally unsustainable.

The Strategic Matrix of Systemic Failure

As surplus nations (the builders) reassert mercantilist strategies and weaponize trade, deficit nations are caught in a trap. They cannot compete on production, and they cannot stop consuming. Their only options are:

Issue more debt, or

Trigger unemployment and social unrest

So they issue debt. And with every round of deficit financing, they grow more dependent on their creditors—economically, politically, and strategically.

Why Empires Collapse Instead of Reforming

When administrative systems sense that they are losing control, their instinct is not to decentralize—it is to consolidate. The people who populate those systems do not believe in radical change, because their legitimacy depends on preserving what exists.

This is why managerial elites respond to systemic decline by doubling down on bureaucracy, legalism, and technocratic control. Not because it works, but because it is the only thing they know how to do.

But history is unambiguous: When empires respond to decline by consolidating power rather than decentralizing it, they don’t reform. They collapse—or go to war.

A Change Management Rooted in Subsidiarity

If centralized, managerial systems are structurally incapable of initiating transformation, then the response must be structural as well: a deliberate effort to rewire how decisions are made, who makes them, and at what level.

The lesson from history, as seen in the Prussian military under Frederick the Great, is that decentralization—specifically the principle of subsidiarity—unlocks efficiency, motivation, and adaptability. This principle, which empowers decision-making at the lowest effective level, was key to Prussia’s improbable military victories and economic growth. It offers a blueprint for addressing the challenges Norway must work its way through to establish resilience in a more volatile international environment.

But subsidiarity alone is not enough. It must be paired with the logic of effective change management, which recognizes that successful transformation follows a specific trajectory:

Create urgency: Systems do not change until remaining the same is more dangerous than evolving. The illusion of control must be broken—by demonstrating that the cost of inaction is collapse or irrelevance.

Form a coalition of builders: Change begins with a minority—those capable of conviction, direction, and adaptive risk. These actors must be identified, protected, and given operating space outside traditional hierarchies.

Decentralize responsibility: Push decision-making power down and outward. Align authority with competence. Replace command-and-control with trust-and-execution.

Attack complexity with simplicity: Central systems defend themselves through procedural density. Builders operate through clarity, focus, and purpose. Codify the mission in simple, measurable terms—and repeat it relentlessly.

Deliver tangible results fast: People support change when they see that it works. Early wins must be real, local, and visible. Bureaucracies fall when legitimacy shifts from titles to outcomes.

Institutionalize autonomy: Don’t merely change the people—change the rules. Embed feedback loops, local control, and strategic slack into the system. Make decentralization irreversible.

This approach demands a philosophical inversion of how power is viewed: from something to be concentrated and defended, to something to be distributed and earned.

From System-Centered to Mission-Centered

True transformation requires a shift from system-centered governance to mission-centered leadership. Managerial elites manage systems. Builders mobilize missions. This is not merely a semantic difference—it is a complete reorientation of structure, incentives, and legitimacy.

In mission-centered models:

Success is defined by outcomes, not compliance.

Authority flows from contribution, not position.

Momentum is sustained by belief, not enforcement.

Final Implication

If we accept that empires collapse when they consolidate in the face of decline, then we must also accept the inverse: that renewal requires dispersal.

The task ahead is not to reform centralized systems by pushing harder from the top. It is to decentralize power, elevate builders, and reconnect purpose with authority.

Only then can energy, innovation, and sovereignty return to the system—bottom-up, builder-led, and strategically aligned with the challenges of the 21st century.

5. Strategic Assets: Untapped Leverage

Despite growing institutional rigidity and an elite class increasingly aligned with the logic of decline, Norway retains strategic assets that matter in the new global order—and which few other Western nations possess. These are not just economic resources; they are geostrategic levers in a world defined by energy, sovereignty, and material power.

If deployed with clarity and intent, these assets could reposition Norway not as a peripheral actor, but as a sovereign outlier—resilient, essential, and independent in a fractured world.

Energy: Sovereign, Stable, Exportable

Norway’s energy system remains its single greatest asset. It is:

Sovereign: Resource ownership and national control remain intact.

Stable: Low corruption, high regulatory predictability.

Exportable: Europe depends on Norwegian gas—especially post-Russia.

As the world moves into an era of AI-driven industrialization, energy availability becomes more valuable than ever. Nations that can deliver stable baseload power—especially renewables, hydro, gas, and ammonia—will anchor global supply chains.

Norway is uniquely positioned to serve:

Europe’s strategic energy needs

Heavy industries; raw materials, steel, aluminum, chemical production, shipbuilding and repair

Data center and AI infrastructure requiring clean, abundant power

But this advantage is perishable. Without a long-term sovereignty doctrine, Norway risks being treated as a utility—rather than a strategic partner—by larger powers.

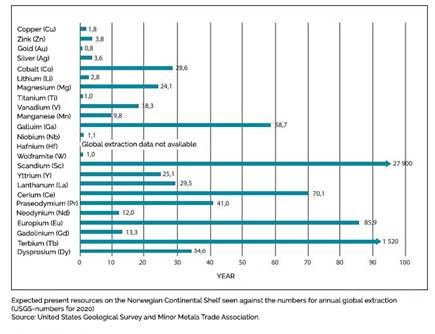

Minerals: Seabed Access in a Material War

Norway’s continental shelf holds one of the most underappreciated concentrations of critical minerals in the Western world—resources essential to the production of green energy infrastructure, defense systems, semiconductors, and advanced manufacturing technologies.

According to 2020 estimates from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), current known resources (Norway is in the early stages of its exploration phase) on the Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS) could, on their own, meet global demand for:

Scandium – over 27,000 years

Terbium – over 1,500 years

Europium – over 850 years

Other strategic elements such as Gallium, Dysprosium, and Praseodymium – for multiple decades

These minerals are strategic bottlenecks in tomorrow’s economy—embedded in the supply chains of everything from electric vehicles and submarines to hypersonic missiles and quantum computing. Today, most of these elements are controlled by China, often through vertically integrated, state-backed monopolies.

The unified West remains critically dependent on access to these materials: rare earths, cobalt, manganese, titanium, copper. The strategic vulnerability is clear.

And Norway is uniquely positioned to shift the balance.

The Norwegian continental shelf contains vast, underexplored marine mineral reserves.

Norway is one of the first Western nations to legalize seabed mineral exploration—a strategic move few others have had the foresight to take.

Situated at the intersection of Atlantic trade routes and the Arctic, Norway is one of the only jurisdictions that combines resource abundance with political stability and Western alignment.

If developed with strategic intent, this domain can serve as more than an economic opportunity—it becomes a pillar of Western material sovereignty.

By building out seabed extraction capabilities, Norway can:

Reshore strategic supply chains critical to national and allied resilience

Reduce Western exposure to authoritarian-controlled mineral monopolies

Set global standards for sustainable and secure seabed resource governance

In a future defined by material competition, Norway’s seabed is not a periphery—it is geopolitical capital.

Deep Sea Mining as a Dual-Use Domain

Beyond economic leverage, Norway’s seabed mineral strategy unlocks another layer of strategic relevance: persistent, full-spectrum environmental monitoring.

Effective deep-sea resource management demands high-resolution data across temperature, salinity, sound, current, light, and seismic variables. When scaled across extraction zones along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge—especially the Fram Strait and Mohn Ridge—this infrastructure creates peripheral sensing capabilities over one of the most sensitive submarine transit corridors in NATO's area of responsibility.

In effect, a well-managed Norwegian DSM industry could grant NATO-aligned forces a standing sensor net over the primary ingress/egress routes for Russian Northern Fleet assets—while denying similar capabilities to authoritarian rivals.

If this capability were developed or operated with poor control, it would risk exposing NATO submarine movements. If developed with intent and coordination, it becomes a strategic bastion—enhancing the West’s last remaining asymmetric advantage: nuclear stealth at sea.

This dimension demands deeper integration between U.S. and Norwegian military planners, intelligence actors, and industrial partners. The seabed is no longer just an economic zone—it is a contested domain of strategic intelligence.

Maritime Power: Leverage in Global Logistics

Norway quietly maintains the 5th largest merchant fleet in the world, backed by world-class maritime insurance, shipping finance, and technical knowledge.

In a world of naval chokepoints, contested sea lanes, and logistical fragility, this is real power.

Arctic navigation will expand with ice melt—Norway is positioned to dominate northern access.

Global shipping redundancy will be increasingly demanded as trade routes fragment.

Norway’s fleet and port infrastructure can be leveraged for national resilience, not just profit.

But that requires shifting from a passive maritime rentier model to a strategic maritime doctrine—linking the fleet to energy security, defense logistics, and foreign policy.

Space Infrastructure: Arctic Sovereignty at Altitude

Norway’s geography offers a unique strategic position in space:

Andøya Space Center provides a sovereign launch site at high latitude.

Svalbard is a vital node for polar-orbit satellite downlink and Arctic surveillance.

In a world where space is becoming militarized and commercialized, Norway controls a slice of orbital geography that few others can replicate.

This matters for:

Climate monitoring

Arctic security

Communications sovereignty

NATO-aligned space infrastructure

But it is underutilized—lacking strategic funding, international branding, and national doctrine.

Geopolitical Location: Strategic by Default

Norway is:

A founding NATO member

An Arctic power

A reliable partner outside the EU core

This gives it freedom of maneuver. Norway is not bound by Brussels bureaucracy, yet remains embedded in the West. Its geography offers a gateway to the Arctic and a flank to Russia.

In the emerging multipolar competition over energy, logistics, and materials, Norway holds a pivotal position. But to use it, Norway should stop behaving like a subcontractor—and start behaving like a sovereign actor.

Assets Without Strategy Are Just Inventory

Norway possesses structural advantages that are rare in the current global landscape. But strategic advantage is never about what you have. It is about what you use.

Without a national strategy built on sovereignty, leverage, and resilience, these assets will either:

Be exploited by others,

Be sold off piecemeal, or

Be buried under our own administrative passivity.

Norway is one of the few nations with the raw ingredients for true autonomy in a fractured global order.

Despite institutional decay, Norway still holds cards that matter in the new global order:

Energy – Stable, sovereign, exportable. Uniquely positioned for green transition and high-energy tech (AI, refining).

Minerals – Continental shelf access to critical mineral resources. One of few Western nations opening marine minerals.

Maritime Power – 5th largest merchant fleet. Arctic navigation potential. Global shipping redundancy.

Space Infrastructure – Andøya and Svalbard offer Arctic launch, surveillance, and comms potential.

Geopolitical Location – Strategic NATO flank and Arctic gatekeeper. Reliable outside EU core fragility.

6.The Doctrine of the Builder State

From Volume to Velocity

In times of systemic stasis, the only force capable of reversing decline is not a better process, but a better purpose. Norway does not suffer from a lack of resources, institutions, or intelligence. It suffers from a lack of conviction, direction, and leadership. The managerial state cannot reform itself. Only a doctrine of builder-driven renewal—anchored in subsidiarity and strategic purpose—can replace it.

From System Survival to National Renewal

For decades, Norway’s governing model has been optimized for stability, predictability, and compliance. Its structures—both political and administrative—have promoted continuity over adaptability. This model succeeded in times of global expansion, low volatility, and institutional trust. But in today’s age of fragmentation and velocity, it has become a liability.

The future will not reward those who manage stasis. It will reward those who can build, reconfigure, and reassert sovereignty—strategically and with conviction.

Renewal begins by rejecting the premise that systems change themselves. They do not. People do.

Change is Leadership-Centric, Not System-Centric

Change is not the result of bureaucratic evolution—it is the result of intentional leadership. And not just leadership at the top, but a distributed architecture of leadership that aligns individuals with mission rather than compliance.

As in Kotter’s frameworks for organizational transformation, momentum is only created when enough people believe in a new direction and are empowered to act on it. But unlike corporate change, national renewal also demands a re-foundation of meaning, identity, and shared responsibility.

In this light, subsidiarity becomes the central operational principle. It distributes authority to those closest to the problem, where real feedback exists, where decisions matter, and where results are visible. It turns spectators into actors—and actors into stewards of change.

A nation cannot be steered through hierarchy alone. It must be animated by builder energy—from every layer, acting in concert, without waiting for permission.

The Conditions for Builder State Emergence

To move from stagnation to strategic renewal, five enabling conditions must be established:

A clarifying national mission

A purpose clear enough to mobilize, bold enough to inspire, and grounded enough to act on. Missions should not be written by committee, but spoken clearly by those who see further. This is where strategic leadership must begin.Distributed power through subsidiarity

Subsidiarity is not decentralization for its own sake. It is functional decentralization—anchored in competence and proximity. Power must flow to where problems are best solved, not where careers are best defended.The institutionalization of trust and responsibility

People rise to responsibility when they are trusted with it. A builder state designs systems that reward contribution, eliminate unnecessary layers, and allow velocity to re-enter public life.A new class of leaders—selected for conviction, not credentialism

Bureaucratic leadership selects for caution and conformity. Transformational leadership selects for courage, clarity, and the will to build. Norway must deliberately elevate a new cadre of actors with builder instincts and national loyalty.An ethos of purpose over process

The function of institutions is to serve the mission—not the reverse. In a builder state, legitimacy is redefined by outcomes, not rituals of procedure. The energy of a nation expands when purpose returns to its core.

Builders vs. Administrators: A Strategic Divide

Norway's administrative elite are not malicious. They are simply the product of a system designed to reward obedience and incrementalism, not transformation. They are system-loyalists—trained to preserve, not to reimagine. When confronted with decay, their reflex is more control, more process, more caution.

But history rewards a different archetype in periods of rupture: the builder.

Norway’s future will not be rebuilt by those who excelled in the old logic. It will be shaped by those willing to exit it—and build anew.

From Meritocracy to Meaning

The managerial class emerged from a belief in meritocracy: the idea that those who succeed within a system deserve to lead it. But when systems drift from their purpose, this principle mutates into system-loyalism. Loyalty replaces clarity. Advancement replaces service. And society is left without people capable of seeing—or challenging—the structure itself.

The most important projects in history were not born from requirements documents. They were born from the will to win. This is the difference between managing for efficiency and building for destiny.

The Role of Vision in Expanding National Energy

National energy is not a finite resource—it grows when people feel connected to a vision larger than themselves. The key to triggering transformation lies in:

A clear and shared national goal

A sense of belonging to a meaningful mission

Trust and responsibility distributed to the edges

Small wins, visible and celebrated early, creating a sense of forward motion

This is the psychological infrastructure of nation-building.

People do not act because they are told. They act when they believe. And belief must be earned by clarity, proof, and shared consequence.

Final Doctrine

Norway must transition from a system-centered, administrator-driven state to a mission-centered, builder-driven nation. This doctrine rests on three pillars:

Subsidiarity as Strategic Operating Principle

Push decision-making power to the lowest competent level. Collapse unnecessary layers. Connect authority to accountability.Builder-Class Leadership

Promote those who are oriented toward action, conviction, and national mission—not those who mastered bureaucracy.National Mission as Organizing Logic

Let everything—budgets, reforms, education, defense, diplomacy—align around a singular, sovereign goal: national reconstitution for resilience in a post-global era.

When a nation gets its power structure right—and ties it to a clear mission—momentum becomes exponential. Norway still holds enough raw leverage to become a sovereign Arctic cornerstone of the Western alliance. But that will only happen if the system is rebuilt around those who can build.